Hollie Smith

How have advancements in technology over the past 100 years changed the way varying creative practitioners make and distribute work?

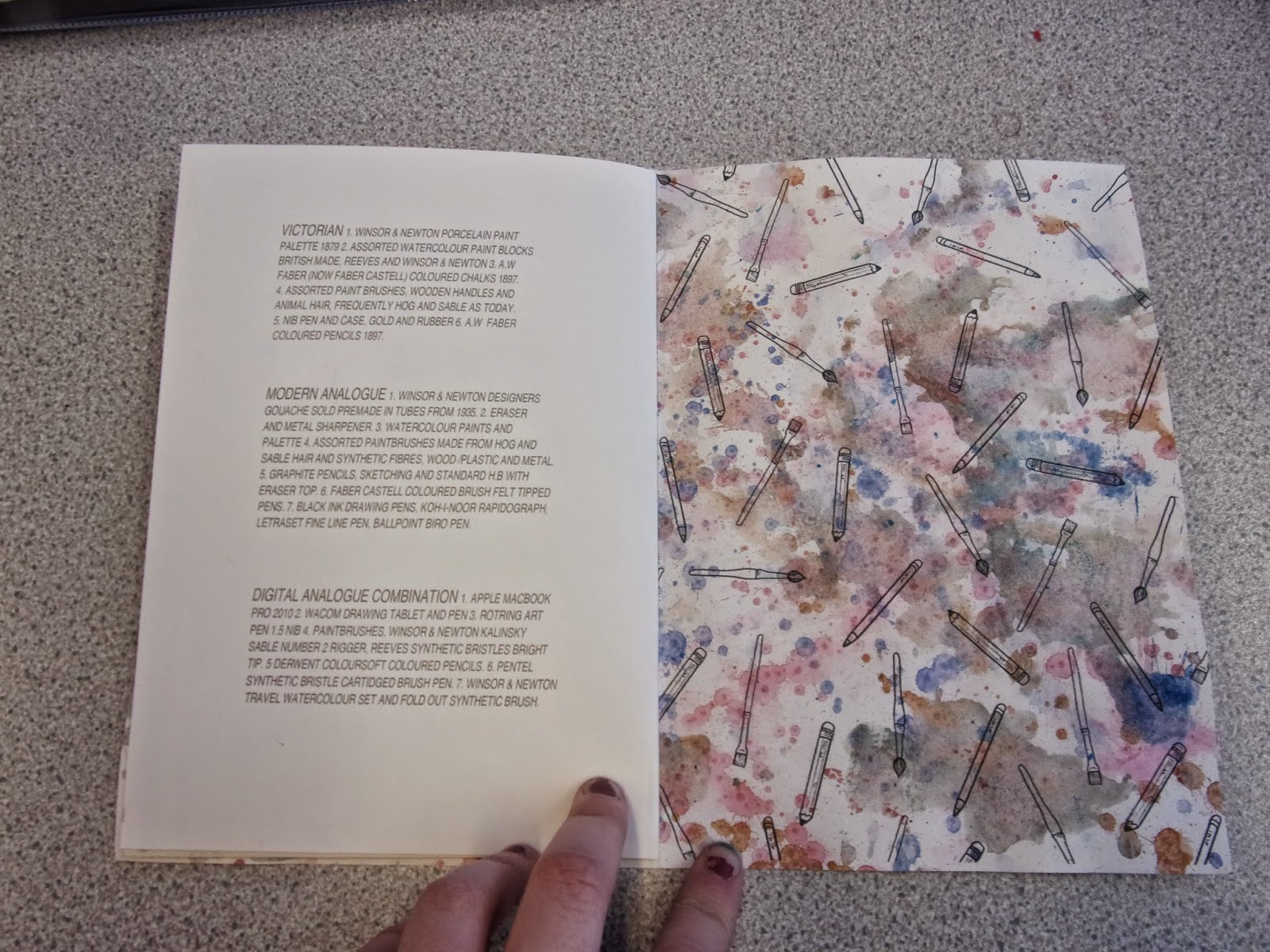

Over the past century developments in technology have inevitably reshaped every facet of daily life and continue to do so with each new discovery. These advancements in technology have heavily effected creative practice, from process to production and even the way the work is seen, valued and interpreted. Obvious factors changing the discipline are the invention of computer, digital drawing programs spearheaded by the launch of Adobe Illustrator, drawing tablets, and even just developments in the engineering of drawing pens. Progress in home and industrial printing, the digital camera, by extension the phone camera, and the rising popularity of applications like Instagram have reshaped the way the work of practitioners is viewed and valued by a wider and more diverse audience. Arguably these changes have been most prominent in the discipline of graphic design because of the invention of the digital typeface and desktop publishing programs, and as a result the strongly related area of illustration has been equally transformed.

It could be argued that the ways we experience art forms with the help of digital technology decrease the value of that artwork. A photograph of a drawing does not bear the same resonance that the original drawing would because it is no longer exclusive to a specific time and place. The barriers between the viewer and the work are broken down and reproduced in the form of a screen. Benjamin (1936) said of this ‘Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be’. Despite this being in reference to printed reproduction it remains true of screen based reproduction, if not to a greater extent because a screen based image does not even occupy the physical space a printed image does.

Herein lies one of the many perceived problems with the artwork in a digital format, whether it be made or merely presented in that manor. Its lack of object permanence makes the digital artwork ethereal and therefor disregarded by many in the art community.

The following discussion will examine the ways in which the creative processes in illustration has developed as a result of technological development and whether, despite the practical benefits, this has in any way devalued the resultant works.

Traditional analogue process can be defined as the production of work using only non-digital. It is work that is tangible and made with physical contact between the hand and the surface. It is an inherently laborious act and it may take years to master just one tool in the analogue spectrum but the result is the pride of mastering a craft and the demonstration of this in a tangible manifestation of that skill. Many argue this is the reason for the perceived value of some traditional work, the spectacle of a skill finely tuned and exclusive to the individual who created it.

Illustrators using solely digital tools to draw are arguably neglecting these skills that artists across centuries have worked to perfect. If their digital toolset were rendered inaccessible they would potentially have no basic skills to rely on, since the tool a digital illustrator has mastered will cease to exist if unplugged. To replace traditional craft with this new impermanent skill set would be would be wasteful of the thousands of man-hours contributed to perfecting the creation and use of those tools.

Some would say it is not such a problem for a skill to be mostly forgotten if it has become obsolete. There are things that can be done with the Photoshop toolbox that one would have to defy laws of physics to recreate by hand, but it could be suggested that each of them is in some way a mixed blessing.

The ‘undo’ tool is an invaluable luxury that perhaps all digital dabbling practitioners wish could be transferred into the analogue process. It eliminates the hazardous mess and inevitable frustration caused by an eraser and prevents the disaster of rogue brush strokes. Devised by the Xerox PARC Bravo in 1974, Miller and Thomas of IBM (1977) stated that “It would be quite useful to permit users to ‘take back’ at least the immediately preceding command by issuing some special ‘undo’ command.”, and thus it came into use.

Undo allows for seamless error free image creation and guarantees that no mark made is in any way permanent, so because of this it can be argued that features such as the undo, the marquee and resizing tools and any of these safety nets for mistakes that should be permanent, have made the process too easy. There’s no risk involved with making an ephemeral mark and therefor no reward to be reaped from the unexpected success of said risk. As Holloway (2005) writes ‘The recognised "Happy Accident", the "Ah Hah," has been the lynch pin of abstraction in painting since well before the advent of the abstract expressionists.’ With these accidents eradicated by ‘undo’ there will never be unexpected development in a drawing, it can only remain within the realm of the imaginable. What’s more, many students who have always worked with predominantly digital tools are often reluctant to commit marks to paper when presented with traditional mediums because they are not accustomed to the permanent nature of the analog drawing process, thus leaving the basis of their practice stilted and underdeveloped.

One of the most important features in Photoshop, and other digital drawing programs, is layers. Resembling the process of screen-printing, layers allow one to place independent images on top of each other to combine and make a completed image. This is a process that is difficult to replicate without the use of a computer, as paper is not typically transparent. The closest similarity would be overlaying components of a collage, but these images are static and confined to the shapes they are produced in, not constantly editable like the digital layers. There are infinite uses for this facility but one in particular is the comics process of Alison Bechdel. In an interview about her process (see image 1) Bechdel explains she creates the ink line work and tonal shading separately and combines the two images on screen to make a neater and more polished looking image. Granted this effect could be achieved entirely with ink in one image, but Bechdel’s process eliminates unnecessary risk. Some would consider this cheating by being too easy but it is understandable in this scenario wherein the comics writer has to produce hundreds of drawn images.

As much as the influx of digital practitioners could be the downfall of traditionally skilled artists, it cannot be denied that the use of a digital drawing package is a skill in itself. The available tools may be mostly ghosts of once revered crafts but the manipulation of these tools is a new skill set just like any other and if a purely traditional practitioner were presented with a Wacom tablet and Photoshop, one would assume they’d struggle just as much if not more than the digital practitioner presented with a brush.

Digital art began with the release of Adobe Illustrator in 1987. It was created to interpret PostScript codes for vector graphics as it had been quite successful alone but due to the complicated programming it could only be used by trained individuals. Illustrator made the codes into imagery on screen so they could be manipulated visually by anyone who could control a mouse. There were skeptics but eventually its potential won the majority over, especially after Adobe ran invitational sessions called ‘Influencing the Influencers’ where they asked esteemed members of the creative world, such as David Hockney, to come and try the new software. As Zeegen (2005) describes it ‘The digital revolution took no prisoners. It was clear- adapt or die!’. Countless aspects of the creative’s lifestyle have been affected by Adobe Illustrator, especially graphic design. It could be used to create and manipulate typefaces and layouts, things that could have taken hours before, such as shuffling the arrangement of a board or resizing an image, could now be done in a matter of seconds. Even so, many still missed the tactile approach to design they’d grown to love. Zeegen goes on to mention the nostalgia many creatives hold towards their old practices ‘Looking back at life before the revolution, albeit with rose tinted glasses, the working day for your lone illustrator was a fairly simple affair’ Indeed before the days of desktop publishing software, designers had to hand draw and paste type onto boards with various dangerous tools and chemicals, to be presented and photographed before finally being printed. Schneider (2012) recalls the process, ‘It started with a layout board. A pre-printed board with non-reproductive blue lines...which meant a stat camera wouldn’t see the lines when shooting Photostats. These were then pasted on more layout boards, to be shot again into film, that would be turned into a printing plate to print a magazine, poster, or flyer. Naturally, this process took about one thousand times longer than what we now do with simple strokes and keyboard commands on computers and are either digitally printed or go live in digital format onto the web.’ The latter statement outlines a factor of digital designing that creates a dichotomy between many practitioners. On the one hand the amount of time saved is the greatest benefit computers have to offer us. They take every aspect of an action and reduce the time it takes by half at least. This was a wonder for publishing companies as it meant they could print more, faster and cheaper, and it meant the designers could get more work done and thus earn more money. Despite this convenience many retaliated against the change. It meant it was too easy; it was no longer a specialist skill one needed to be trained in. Anybody could sit at a computer and create professional looking graphic design in an instant. Of this Bert Monroy (2014) said ‘Everybody said you’re going to ruin good design because now anybody can do it, but the cream rises to the top. The creativity is in the designer, the creating is in the person who uses the tools.’ In support of this, rather than claiming graphic design has been made easy it could be seen instead as a raising of the bar for the base level of designing ability, meaning the visual quality of the output of an untrained designer is now much better than it used to be but the level of visual quality in the work of a trained professional would be better than the untrained designer in the same proportion to before. In support is Burgess’ (2005) point ‘Digital technology is exciting but only as exciting as the ideas you have inside your head...It is really all about trying to produce work that is distinctive and original, whatever that is.’

A similar transformation occurred in the discipline of comic making, because of its inherent similarities with graphic design in the formality it’s layout. In days before computers, drawing a comic page was as complicated as creating a design board. McCloud (2006) details this in the informational graphic novel Making Comics ‘A T-Square and triangle help rule parallel and perpendicular lines like panel borders and captions and a straight edged metal ruler will come in handy for measuring and drawing other straight lines, and for guiding your cutting tools’ Drawing even further similarities with graphic design is the drawing of the panels and text ‘A T-Square was used to keep the guidelines parallel and an ‘Ames Guide’ slid back and forth as a pencil was placed in a succession of holes to produce as many guidelines as needed. Many cartoonists today use a font or just letter freehand, but you can still find loyal users of the Ames guide system and their work can be both consistent and attractive.’ Perhaps some continue to use traditional methods for both panel borders and text because it creates an organic hand made aesthetic no systematic computerised font could achieve. The visual quality is far more authentic and tangible. An example of this is the comics of Jack Teagle (see image 2), often drawn in basic tools his border lines are loose and informal which gives the work a different tone to a digital, mechanised border, or even an immaculately drawn ink border. There remains variation within the traditional pathway, including in the toolbox.

There are many time honored tools favored by comics artists, as McCloud goes on to describe, ‘For planning and penciling, most use a light (i.e. hard) mechanical pencil, a non-reproducible blue pencil, a smooth gum eraser and/or a more abrasive but less greasy pink eraser. To create black lines for mechanical reproduction a variety of tools have emerged over the years and become industry standards.’ He goes on to discuss the three most commonly employed tools; the sable brush, the nib pen and the fixed width technical pen and the differences in their line qualities. This is something that cannot be replicated by a computer. The line on screen is a programmed formation of pixels and cannot share the unpredictable physical nature of real ink on real paper. For this reason many older comics artists, such as Robert Crumb, insist on using only traditional tools. Crumb, in fact, has a penchant for antique art materials and claims ‘They’re all getting harder to find, all these antique art instruments. The companies that have made them are dying off one by one…They last and last, …. I’ve still got maybe fifty of those. I think they’ll probably last me the rest of my life.’ His chosen set of tools, which he explained in an interview, includes a crow quill ‘ I use what’s called a crow-quill pen. An old steel-point nib, that’s what I use to draw with—for my artwork, I have to use antique, archaic tools.’, and a very specific hierarchy of paper ‘Well, I use the old Strathmore vellum surface paper, which is the best paper you can get in the Western world for ink line drawing. It has a good, hard surface. I have it mailed from the New York Central Art Supply in New York. For a while I was using this old Strathmore paper from fifty years ago that some guy sent me, it had bad comic art on one side, hacked-out comic work from 1960, but the paper is superior to anything you can get now.’

Cartoonists such as Crumb who were already prolific a long time before the turn of the digital era are often inseparable from their life-long loved processes. The work does have a different visual quality than that made by digital creators but it can be difficult to tell if this is due to the creator or the tool, especially when there are yet to exist examples of some older cartoonists using the digital tool set. Without this it is difficult to make a fair comparison between the tools. Although by simply comparing the aesthetic quality of two examples, Genesis Illustrated by Crumb (see image 3) and Scott McCloud’s web comic Proto the Pet (see image 4) in his Morning Improv series, there is a clear difference. Crumb’s illustrations are masterful, considered and visually balanced, as well as characterful in the erratic, scratchy quality of the lines and the intricate detail within them. McCloud’s however are clearly confused with the remedial yet at-the-time exciting visual possibilities of the digital drawing program. The lines are embossed in the way Macromedia Fireworks used to encourage, the dated backgrounds and acrid colours clash dramatically and the font selection is juvenile and tacky. By this comparison one could draw the conclusion that digital and web based comics are a blip in the history of image based story telling but in no way is it a fair comparison to even be making. Scott McCloud’s work extends infinitely further than this questionable comic strip and his work into the digital and online development of the comics medium is indispensable. The incomplete three-part web comic ‘The Right Number’ (see image 5), begun in 2003, was fascinating in its understanding of the capabilities of the digital format. The comic replaces the moments of space between panels on a page with a fluid zoom into the next through the center of the image, where afterwards a minuscule version of the following panel can be seen, which eradicates the stunting break of turning a comic page and the momentary break of flicking ones eyes across the page from one panel to the next. This results in a dynamic and seamless reading experience, which is wholly immersive and would be inconceivable to produce using only traditional tools and presentation. He also used the new online payment system of the type

‘Bitcoin’ demonstrating another way in which the creative practitioners life has been changed by the Internet, more advanced payment systems that allow for simple online vending.

McCloud said of the work ‘Although ‘The Right Number’ was an experimental story in an experimental format (originally using an experimental payment system) I like it as a story and I hope you will too.’

He also pioneered extra online content in comics with chapter 5 1/2 in Making Comics where extra pages were featured exclusively online and initiated the idea of the infinite canvas on-screen that aims to see the screen as a window rather than a page and disregard the physical constraints of working on real paper. The infinite canvas has even been used in physical media with Luke Pearson’s contribution to the V&A exhibition Memory Palace in 2013 (see image 6) wherein the ‘infinite canvas’ comic was pasted onto a large white wall. Despite this there remains inerent value in a completed comic board. McCloud (2006) says ‘A good page of original art can be an object of tangible beauty and lasting value’, one of the most unavoidable criticisms of the digital format; it is not tangible.

The conclusion to be drawn from this is that digital and analogue are mostly equal in their advantages and disadvantages, but they are two completely different sets of tools. There is no way to compare the two fairly because they are of a completely opposing nature and are not mutually exclusive. The most logical way to work with this conflict is to create a synthesis between the two processes so they can each lift up the pitfalls of the other. As Holloway (2005) says ‘The different tones of expression between oils, watercolour, acrylic, pencil, conte, or combinations of these in a piece are paramount to the quality of the final image and its ability to communicate. The substrate one chooses to work upon has everything to do with the final presentation and interpretation of the completed work. The chosen materials and their manipulation set the tone of the final work and its ability to project the artist's intent. This is no less true with digital media. Having chosen to work through the computer immediately sets a tone to ones works.’

The divide between the two is dissolving so there is no longer a need to choose one side or the other. These programs were made to advance and assist the creative process, not to destroy the integrity of it, but ultimately in a business such as illustration the context of the brief will define the method of image making, and with the continuing advancements in technology there will only end up being more of these methods to choose from.

Bibliography

BENJAMIN, W. (1936) The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction France

MILLER, L.A & THOMAS J.C (1977) Jr Behavioral Issues in the Use of Interactive Systems. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies (1999)

HOLLOWAY, J (2005) Promise, Paradox and Oppurinuty [Online] MOCA. Available from http://www.museumofcomputerart.com/editorial/holloway.asp [Accessed on 25th April 2015]

BECHDEL, A. (2012) The Alison Bechdel Interview. The Comics Journal [Online] Available from http://www.tcj.com/the-alison-bechdel-interview/2/ [Acessed on 25th April 2015]

ZEEGEN, L. (2005) Secrets of Digital Illustration: A Master Class in Commercial Image Making Rotovision, East Sussex

MONROY, B. (2014) The Adobe Illustrator Story Vimeo [Online] Available from https://vimeo.com/95415863 [accessed 25th April 2015]

BURGESS, P. & ZEEGEN, L. (2005) Secrets of Digital Illustration: A Master Class in Commercial Image Making Rotovision, East Sussex

MCCLOUD, S. (2006) Making Comics Harper Collins, UK

CRUMB, R. (2010), The Paris Review Interview by Ted Widmer The Paris Review [online] Available at http://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/6017/the-art-of-comics-no-1-r-crumb [Accessed on April 25th 2015]

SCHNEIDER, S. (2012) Design Before Computers Ruled the Universe, Web Designer Depot [online] Available at http://www.webdesignerdepot.com/2012/02/design-before-computers-ruled-the-universe/ [Accessed on 25th April 2015]